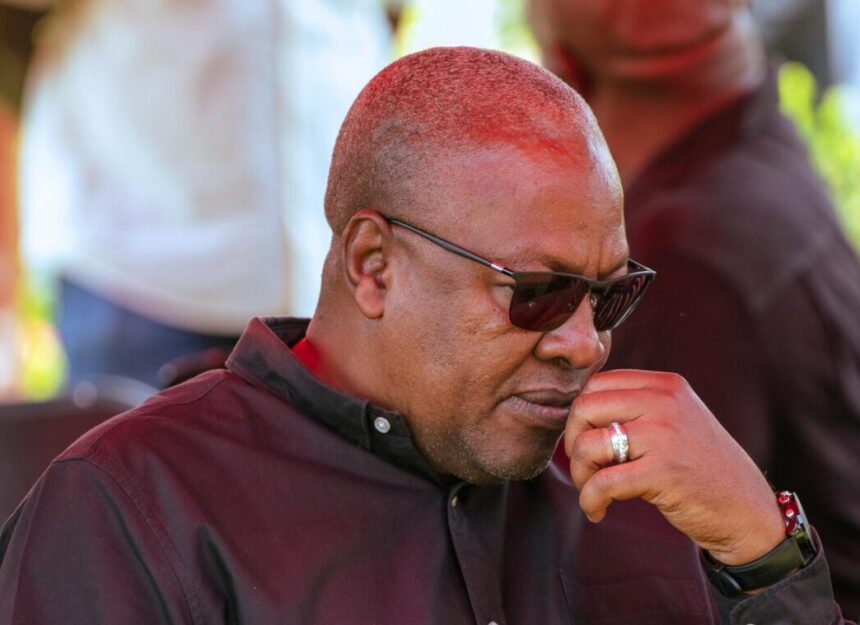

Ghana is witnessing a quiet but dangerous transformation. While many citizens are distracted by the daily grind of economic hardship and political rhetoric, a new legal order is being carefully, deliberately constructed by President John Mahama. Call it what it is: The Mahama Legal System.

It began with the removal of a duly appointed Chief Justice, through a process that can only be described as a sham. In her place, an Acting Chief Justice was installed, who wasted no time orchestrating the removal of his own colleague.

This brazen act has rightly earned him the label #CoupCJ, a judicial coup against the independence of our highest court.

But the project did not stop there. Mahama’s allies moved quickly to establish a rival body: the Ghana Law Society, to openly challenge the authority and standing of the Ghana Bar Association. The troubling part? This is being done with the tacit support of the Coup CJ himself.

For the first time in our history, Ghana is facing the reality of parallel legal associations, one recognized for decades as the professional body of lawyers, and another birthed to serve narrow political ends.

Then we come to the courts, Mahama once criticized President Akufo-Addo for “packing” the Supreme Court with qualified and competent justices. Yet, in the short period since assuming office, he has done far worse. Already, seven new justices have been appointed to the Supreme Court.

Just today, he swore in 21 Court of Appeal judges, and is preparing to install 41 High Court judges, including one already notoriously called the Animal Farm Judge. At this pace, within months, the entirety of Ghana’s judiciary, from the High Court to the Supreme Court, will be firmly under the control of John Mahama.

Piece by piece, Mahama is creating a parallel legal system: a judiciary remade in his image, backed by a rival lawyers’ association, and overseen by a Chief Justice born out of a coup against his predecessor. This is not reform. It is a systematic capture of institutions. It is the consolidation of power through the courts.

The question is stark: Is this what Ghanaians want? A judiciary stripped of its independence and turned into the political arm of one man? Do we want parallel bars, parallel judges, parallel justice? If this is allowed to continue unchecked, unspoken about, the rule of law will be reduced to the rule of Mahama.

The most alarming part of all this is the silence. Many Ghanaians are not paying attention to these structural changes, even though they strike at the heart of our democracy. A compromised judiciary is not just a political problem; it is a national crisis we need to avert. Once lost, the independence of the courts cannot easily be reclaimed.

This is the time for citizens, civil society, and professional bodies to speak up. Democracy is not destroyed in one day; it is chipped away, step by step, while people look the other way. Today, it is the judiciary. Tomorrow, it could be Parliament. Eventually, it could be the very freedoms we take for granted.

Ghana must decide whether we want a legal system that serves the Constitution or one that serves John Mahama’s ambitions. The stakes could not be higher.

P.Y. Atta